INTERNATIONAL AND SPECIALIZED TRANSPORT

■

OCTOBER 2013

THE KNOWLEDGE

41

Alternative ways

As a logical sequel to

the last two articles on

transport and crane

basics this month’s

feature, the fourth in

the series, covers

alternative moving

and lifting techniques.

MARCO VAN DAAL

explains some options

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Marco van Daal has

been in the heavy

lift and transport

industry since

1993. He started at

Mammoet Transport

from the Netherlands

and later with Fagioli

PSC from Italy,

both esteemed companies and leading

authorities in the industry. His 20-year

plus experience extends to five continents

and more than 55 countries. It resulted

in a book The Art of Heavy Transport,

available at:

of-heavy-transport/

Van Daal has a real passion for sharing

knowledge and experience – the primary

reason for the seminars that he frequently

holds around the world. He lives in

Aruba, in the Dutch Caribbean, with his

wife and daughters.

continue rolling on.

One of the challenges was, and even

still in today’s rolling applications, is the

starting, stopping and steering of the load.

It requires a certain force to start rolling,

and once the load rolls it is important to

keep it rolling. For the steering, one would

have to stop the rolling motion, change

the angle of the logs and start rolling

again, all on an inclined surface. To turn

the corner, it is believed that sand was

spread out over a level area then the block

was skidded over it with brute force.

Fast forward

Two moving techniques that are

frequently applied in our industry today

find their roots in the pyramid building

>

C

ranes and modular transporters are

considered conventional tools for

the job but, where they cannot meet

all challenges, an alternative is needed. In

cases where there is a limited footprint,

height restriction or other physical site

constraints, the question, “What if a crane

or transporter cannot be used?” may

arise. The pyramids in Egypt, for

example, would not exist without the

development of alternative lifting and

moving techniques.

This is a good starting point. The

average pyramid consists of 2.5 million

limestone and granite blocks, each

weighing 2.5 tonnes each. More than

6 million tonnes of material has to be

mobilised to build a large pyramid,

sometimes from as far as 800 km

away. Even with today’s equipment

and technology, these are mind

boggling numbers.

There are a few different theories on

how the pyramids were constructed but

they all involve the rolling of each block

via an inclined slope to the final elevation

and destination. The rolling is believed

to have been carried out on logs with

many people pulling on the ropes. The

logs coming out at the rear end have to

be picked up and carried to the front end

where they are lined up for the block to

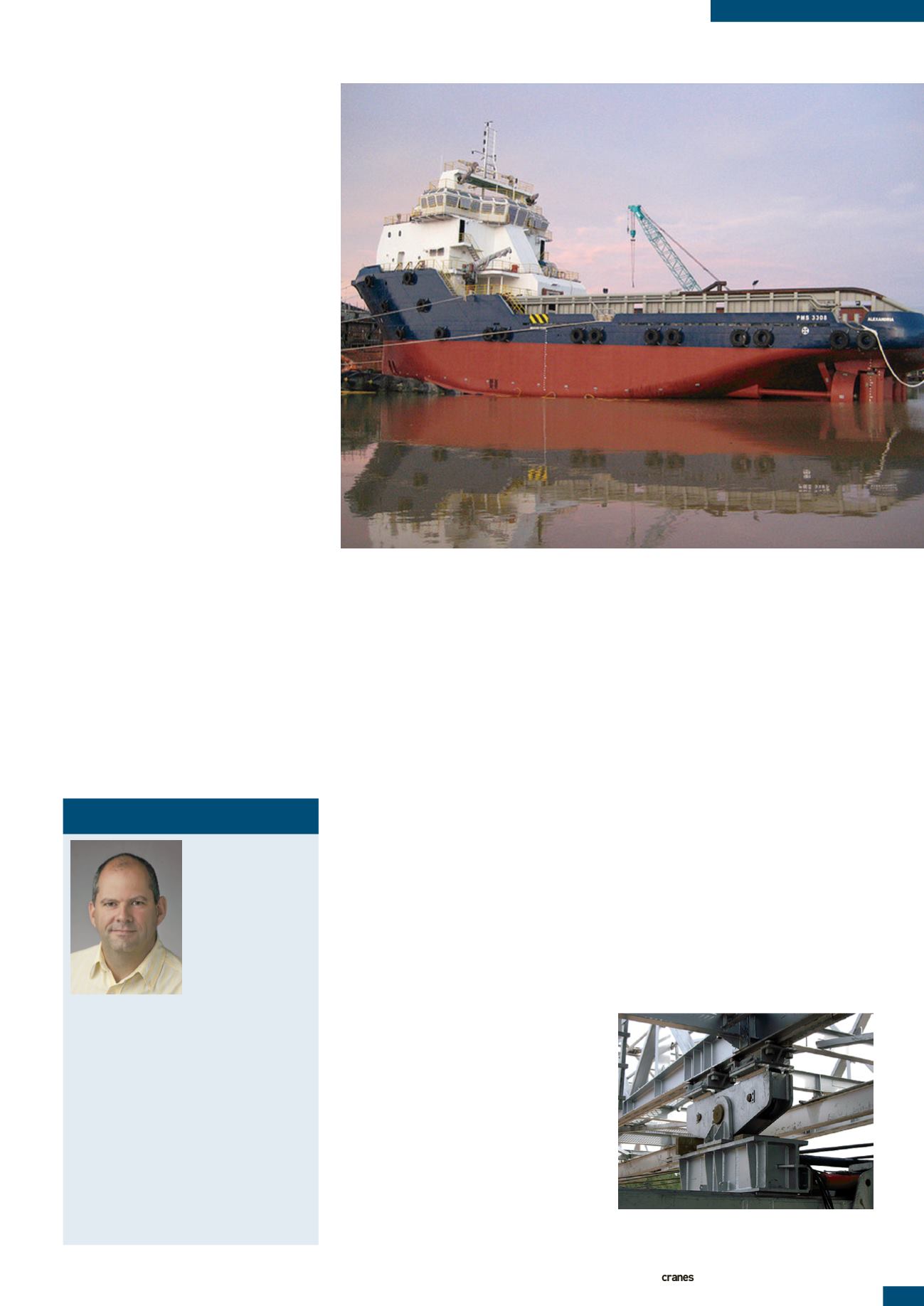

Launching a ship using

pneumatic rubber rollers

Tank rollers to reduce friction in

heavy shift applications